Imagine going through life with only a sliver of the color spectrum, never fully realizing how much you're missing. Last week, a team of scientists announced the discovery of a new color that no human had ever seen before. Using laser pulses aimed directly into the eyes of five participants, they stimulated retinal cells in a way that produced a completely novel color experience—neither blue nor green, but something in between. They called it Olo.*

This wasn’t just a scientific curiosity; it was a reminder that just because we don’t see something doesn’t mean it’s not real. Our understanding of the world is shaped by the limits of language, perception, social norms, coping mechanisms, and inherited frameworks. And often, those limits can obscure things that are hiding in plain sight.

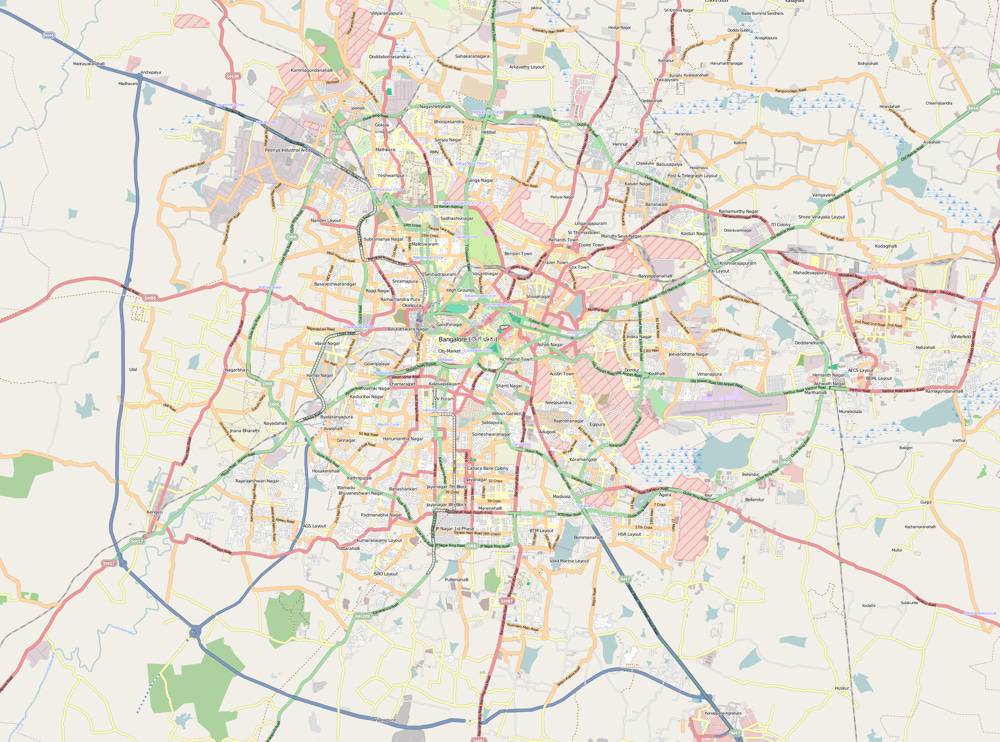

Take urbanization in India.

India’s urbanization is unfolding differently from the neat, linear progression you might read about in textbooks. According to conventional Western industrial history, the model is simple and straightforward: rural villagers move to cities, integrate into structured workforces, and become part of the consumption economy. Anyone who’s traveled to India’s edges knows that this story doesn’t wholly apply.

To start with, migration in India is not just a one-time shift from rural to urban areas; it is a natural, seasonal ebb and flow that mirrors agricultural cycles, festivals, and labor demands. Consider the kharif, rabi, and monsoon seasons, which dictate the planting and harvesting cycles for crops like rice and wheat. During these peak periods, there is a significant demand for agricultural laborers in specific regions, drawing individuals from their home villages in search of work. As the harvest concludes and agricultural activity slows, many of these laborers return to their native places with their earnings. This cyclical movement is also intertwined with social and cultural life: festivals, marriages, and family obligations that often serve as compelling reasons for temporary return migration. Furthermore, the informal economy in urban and peri-urban centers offers temporary employment opportunities in construction or small-scale manufacturing, providing a vital supplementary income for those whose livelihoods are primarily tied to the land. This constant ebb and flow of people is a pragmatic adaptation to the economic and environmental realities that shape livelihoods across India.

I’ve traveled across these places and seen firsthand how this works. This movement isn’t simply about moving from one place to another, it's about shifting in and out as conditions change. This fluidity gives rise to an economic phenomenon that doesn’t fit neatly into the traditional rural-urban dichotomy. It’s the rise of peri-urban India.

Peri-urban is the in-between—not quite city, but no longer rural. These are messy, vibrant zones of economic activity shaped by migration, logistics, and affordability. Think Bhiwandi, Sanand, Hosur, Ranchi’s outer ring, Coimbatore’s industrial sprawl, the outskirts of Lucknow, or the Gurgaon-Manesar-Dharuhera corridor. None of them feature in tourist brochures and many startups aren’t keen to serve them, yet all are critical nodes in the country’s supply chains and labor networks. Take a place like Ghaziabad as a prime illustration. On paper, it’s a municipal corporation. In practice, it’s a fragmented collection of peri-urban clusters—itself straddling the edge of Delhi’s NCR but never quite inside it.

While India’s official urbanization rate is pegged at around 36% (World Bank, 2022), studies from UN-Habitat and others suggest the real urban footprint could be closer to 50% when you account for electrification, construction activity, and migration flows. That missing 200 million people—or one Brazil—aren’t in cities or villages. They’re in-between.

These in-between zones are full of contradictions. Construction is booming but permits and zoning are nonexistent. Online shopping is common, yet addresses are often improvised based on landmarks. Apps deliver Limca but piped water may be absent. Work is abundant but workers are invisible to labor statistics. Industrial sheds sit next to farmland, and informal settlements abut logistics hubs. Autos navigate construction that spills out into the streets and water tankers slosh along. In local markets, vendors sell both mobile phone accessories and fresh vegetables for the evening’s subzi. The lives of residents are similarly hybrid; a young person might commute to a tech job in the city center but return home to a family deeply rooted in tradition and community. This in-between is a dynamic collision of old and new, where the conveniences of urban life are often accompanied by the challenges of inadequate infrastructure and layered with deeply ingrained rural customs.

Are these places just waypoints enroute to some formal urban destination—or are they the destination? The idea of a polished, linear rural-to-urban trajectory doesn’t hold here. Yet India’s governance, credit systems, housing models, healthcare delivery, and even data collection remain oriented toward neat categories—urban or rural, formal or informal.

A Problem of Definitions

The Census of India’s definitions compound the invisibility. Urban is classified in one of three ways:

Statutory Towns: Areas with a local municipal body (municipality, corporation, cantonment board).

Census Towns: Areas that meet all three criteria:

A population of at least 5,000

At least 75% of the male workforce in non-agricultural employment

A population density of at least 400 persons per sq km

Urban Agglomerations: A continuous spread of a core urban area and its adjoining outgrowths, totaling at least 20,000 people.

And rural? It’s everything else, meaning Rural = Not Urban

This binary classification leaves no space for the in-between. It erases places with urban character but rural classification. It ignores the flux of population, the decline of agriculture, and the shift toward services and industry. These areas are often “stuck” administratively, missing out on infrastructure, planning, and visibility, even as they function like small cities.

A Side of Peri-Peri

Peri-urban India falls through the cracks. These areas lie outside municipal boundaries, so they receive no urban services while at the same time remain excluded from rural schemes. Yet, these engines of industry and consumption are home to over 600 million people. Gaps in classification have real-world consequences. Fast-growing zones remain rural on paper and therefore miss out on investment and infrastructure. No one is quite responsible—urban governance is too weak, rural governance too rigid. Some areas deliberately stay rural to access subsidies or avoid taxes, sacrificing long-term infrastructure for short-term gain. And investors, clinging to the usual suspects, overlook these hubs and miss the steady, long-term growth bubbling under the surface.

You don’t need to go far to feel the movement and energy in these transitional zones, and nowhere is the Olo reality more visible than on the outskirts of Bangalore. From Devanahalli’s luxury real estate around the airport to Hoskote’s industrial corridors lined with paying guest hostels (PGs), these areas look urban, act urban, but remain administratively rural. Anekal, on the city’s southern fringe, encompasses parts of Electronic City yet relies on panchayat services. There’s no formal signpost that tells you that you’ve crossed from rural to urban and back.

And that’s the thing—most reports I read or investor conferences I go to still portray India through outdated binaries. India 1, 2, 3. Rural vs. Urban. Formal vs. Informal. Developed vs. Emerging. But life doesn’t work in binaries here. Honestly, it doesn’t anywhere—India’s just more upfront about it.

While the major metros are undoubtedly charging ahead at breakneck speed, with a proliferation of fine dining, coffee shops, breweries, bakeries, and creature comforts beyond imagination, the next India isn’t taking shape among the usual suspects. It is coming together at the edges — on the fringes of cities, in the spaces that were never planned but have grown anyway. In half-finished industrial parks next to fields and truck depots, and in bazaars where cash auctions and QR codes coexist. Away from the spotlight and in the big middle—that’s where the action is.

Can you spot the Olo?

*Maybe you noticed that “olo” is hiding in plain sight—the middle three letters of “color.” It’s been there all along, just waiting for someone to see it.